Why the Far Side of the Moon Matters So Much

China’s successful landing is part of the moon’s long geopolitical history.

Humankind first laid eyes on the far side of the moon in 1968.

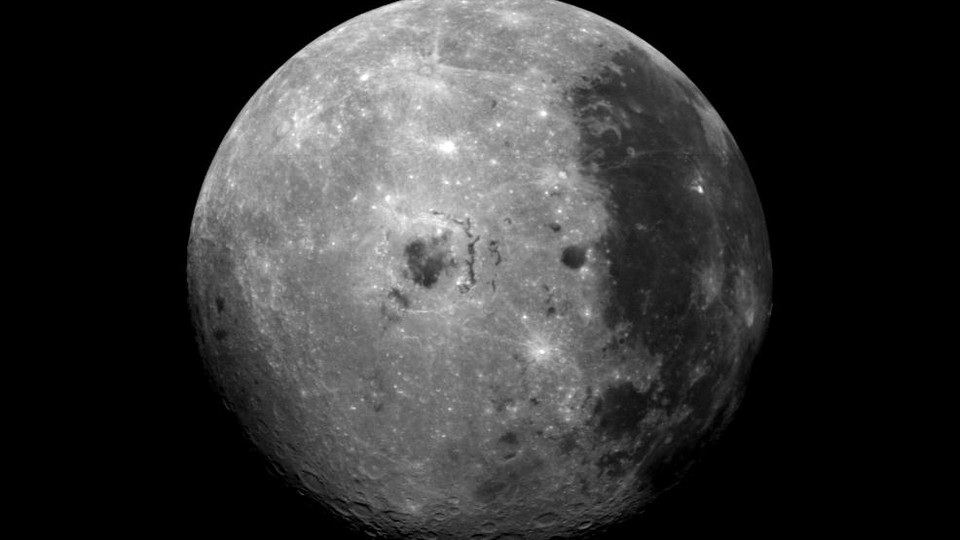

“The backside looks like a sand pile my kids have been playing in for a long time,” the astronaut Bill Anders told NASA mission control. For millennia, people had gazed up at the same view of the Earth’s companion—the same craters, cracks, and fissures. As the Apollo spacecraft floated over the unfamiliar lunar surface, Anders described the new territory, which promised to be a tough landing for anyone who tried. “It’s all beat up, no definition,” he said. “Just a lot of bumps and holes.”

Fifty years later, humankind landed in the sand pile.

China set down a spacecraft on the far side of the moon on Wednesday, Beijing time. On Thursday, the spacecraft, named Chang’e 4, after the Chinese goddess of the moon, unlocked a hatch and released a rover onto the lunar soil. The rover carries tools designed to explore the uncharted terrain, which, thanks to a lifetime of facing the cosmos, is covered in craters.

The landing, celebrated already as an achievement for humankind, is a reminder that people can accomplish some wonderfully wild things, given enough curiosity, skill, and rocket fuel. The first photos from the Chang’e 4 mission, captured inside a crater near the moon’s south pole, are chill-inducing. But the landing is also a distinctly geopolitical win for a nation that hadn’t even launched its first satellite when Bill Anders saw that sand pile 50 years ago.

The story of space exploration, the kind carried out by national governments, began as a quest for national achievement and power. In the 1950s, the Americans and the Russians shot rocket after rocket into the sky with patriotism, not discovery, at the forefront of their minds. Any science that came out of it was a bonus.

Perhaps the clearest illustration of this geopolitical drive is a Soviet spacecraft called Luna 2. The Soviet Union launched Luna 2 in 1959, two years after sending the first satellite into orbit around Earth. Luna 2 was beachball-shaped, with spiky antennas, and weighed 390 pounds. The spacecraft carried multiple instruments designed to measure the radiation environment around the moon. It transmitted this data back to Earth as it flew through space. When Luna 2 approached the lunar surface, mission control held their breath.

The signals stopped. Luna 2 had slammed into the moon, breaking apart into pieces.

Mission control erupted in cheers. For the Soviet Union, it didn’t matter that Luna 2, which became the first spacecraft to reach the moon, had been smashed into smithereens. The point was to get there first—to mark territory. The Soviets had packed the spacecraft with metal pendants bearing the hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union. The impact scattered them across the lunar regolith, where they remain today, as if on display at a museum.

For the United States and the Soviet Union, every milestone in the space race was commemorated as an achievement for all humankind, yes, but also as a gain for the nation—for its government, its policies, its ideals—that reached it first. Two days after Luna 2 completed its mission, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev visited the United States. As the British historian Robert Cavendish wrote in the magazine History Today, Americans suspected that the space mission had been coordinated with the political visit: Khrushchev was “beaming with rumbustious pride” and gleefully “lectured Americans on the virtues of communism and the immorality of scantily clothed chorus girls.”

A decade later, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon, the Soviets were decidedly less rumbustious. Sergei Khrushchev, the son of the premier, told Scientific American in 2009 that Soviet propaganda let the news of “one giant leap for mankind” slide by without much fanfare. “It was not secret, but it was not shown to the public,” he said.

By then, China had already been trying to insert itself into the space race for more than a decade. After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, Mao Zedong instructed his country’s scientists and engineers to prepare a satellite of their own, to launch in 1959, in honor of the Great Leap Forward, the leader’s ultimately failed plan for rapid industrialization. The directive from the top to scientists was simple: “Get it up, follow it around, make it seen, make it heard.”

But the country didn’t have the necessary technology for such a fast turnaround, and space-exploration efforts would be repeatedly derailed by political turmoil in the coming decades. The satellite launched at last in 1970, equipped with a single purpose: playing the first few bars of “The East Is Red,” an instrumental song glorifying China’s Cultural Revolution.

In recent years, though, China’s space efforts have jumped to warp speed. When the country launched its first astronaut in 2003, it became one of only three countries to have done so. It sent an uncrewed orbiter around the moon in 2007, and a rover in 2013. In 2011, it launched a space station that astronauts visited twice before it was decommissioned and deliberately crashed into the Pacific Ocean. A second space station launched in 2016. In 2018, China launched more rockets into orbit than any other country.

China has more bold plans for the future. The country is aiming to land a rover on Mars in early 2021 and, if successful, would become the second country after the United States to accomplish the feat. It also wants to land astronauts on the moon by 2030.

These and other milestones can be celebrated on a global scale as an achievement for the human species, just like the landing was. “It is human nature to explore the unknown world,” Wu Weiren, the chief designer of the Chang’e 4 mission, said in a television interview, according to The New York Times. “And it is what our generation and the next generation are supposed to do.”

But China’s space accomplishments are as symbolic and strategic as the Apollo and Vostok programs were in the 1960s, especially now, when space agencies in Europe, Russia, India, and, most recently, the United States have put a big focus on lunar exploration. “We are building China into a space giant,” Wu said.

For spacefaring nations, impressive feats, whether it’s landing on Mars or on the far side of the moon, will always be seen through the lens of the nation that managed to pull it off. “When you are the first country to land a probe on the far side of the moon, that says something about your science and technology, that says something about your industry,” the Heritage Foundation’s Dean Cheng, one of the few Chinese-speaking analysts in the United States that focus on China’s space program, told The Atlantic in 2017.

If it still seems silly to consider geopolitical history in the exuberant moments after a moon landing, consider this reaction from the Global Times, a newspaper run by the Communist Party, China’s ruling party, reported by The Washington Post:

Unlike mankind’s mania in the past, the Chinese people ultimately harbor the dream of shared human destiny and practices open cooperation. We choose to go to the back of the moon not because of the unique glory it brings, but because this difficult step of destiny is also a forward step for human civilization!

A “forward step for human civilization,” indeed. But the “unique glory” is certainly nice, too.