The Most Powerful Dissent in American History

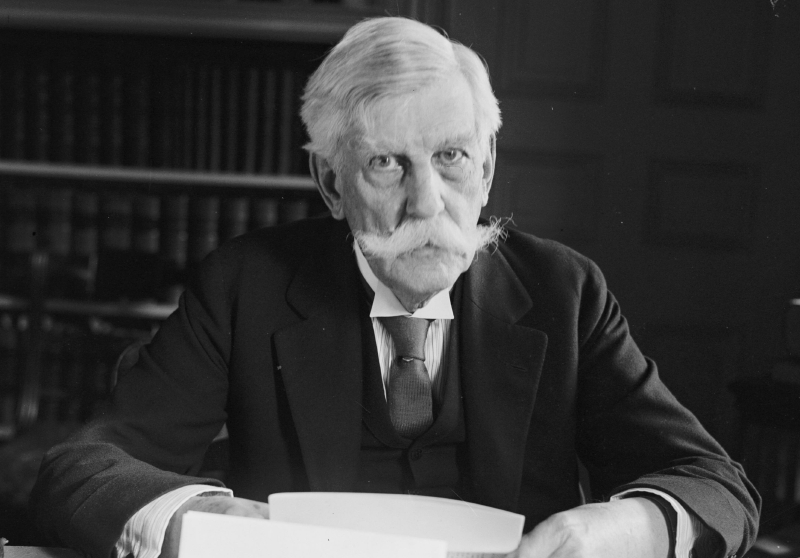

A smart new book reveals precisely how and why Oliver Wendell Holmes changed his mind about the first amendment.

If there is a more relevant or powerful passage in American law, I am not aware of it. Relevant because it expressed a universal concept -- free trade in ideas -- that 125 years after the Constitution was ratified still had not yet taken hold in our democracy. Powerful because it went beyond legal precepts to a fundamental fact of human existence: We all make mistakes. We all have good opinions and bad ones. None of us are right all the time. All of us at one point or another have to respect what someone else says. And life is an experiment from the moment we wake in the morning until the moment we lay our heads down at night.

It's a passage written 94 years ago that both explains and preserves our op-ed pages and the Internet, talk-radio shows, and blogs, in the brilliant blending of two American institutions that were not always destined to go together: the free market and free speech. It's a passage that both acknowledges human weakness and strives to master it, that recognizes the roiling diversity of American thought and seeks to make something clear and profound from it. From United States Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in his dissent in Abrams v. United States:

Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power, and want a certain result with all your heart, you naturally express your wishes in law, and sweep away all opposition. To allow opposition by speech seems to indicate that you think the speech impotent, as when a man says that he has squared the circle, or that you do not care wholeheartedly for the result, or that you doubt either your power or your premises.

But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas -- that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.

That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.

Of course, the story of free speech in America neither begins nor ends with Abrams. But it is a clear pivot point. In that 1919 case, a dispute decided one year minus one day after the end of the first "war to end all wars," the United States Supreme Court sustained the convictions of five Russian-born men who were prosecuted under the Espionage Act of 1917, as it had been amended by the Sedition Act of 1918, for "provoking and encouraging" resistance to the government's war efforts (and its hostile maneuvers toward Russia) through a series of pamphlets.

Such prosecutions would be unthinkable today, not because modern officials embrace criticism more bravely than their predecessors but because we have come as a nation and as a people to acknowledge that the First Amendment's protections are (and ought to be) especially stout when it comes to dissent about the public workings of government. And that nearly universal acknowledgment, which has survived America's four major wars since World War I and guides the way we both conduct business and handle our own personal affairs, was born in Justice Holmes' dissent.

Just in time for your August beach reading, Thomas Healy, a former federal appeals court law clerk and reporter for The Baltimore Sun, has written an excellent book about how Justice Holmes, perhaps the most famous and influential justice of all time, came to write this passage -- and came around, at last, to a rousing defense of the First Amendment. Titled The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind-- and Changed the History of Free Speech in America, the book is a fascinating glimpse into an art that seems lost in law and politics today: the art of changing one's mind.

In meticulous detail, Healy tells us how the great jurist, who had staunchly upheld criminal convictions in free speech cases just months before, changed his mind in Abrams. He changed it because of an intense lobbying effort by his political friends and fellow judges. He changed it because he had been reading the work of legal and political philosophers in Europe, both living and dead. He changed it because he came gradually to realize how broadly the Justice Department was relying upon federal statutes to punish even that dissent which was obviously unlikely to undermine the government's ability to function.

Healy begins his book with an anecdote about a visit Justice Holmes received at home from three of his fellow justices, after he had distributed his dissent in Abrams but before he would publicly announce it. What transpired in that meeting isn't just "a remarkable piece of constitutional history," as Healy puts it, but remarkable for what it suggests about the way the Supreme Court does (or does not) operate today. Can you imagine Justices Scalia, Thomas and Alito visiting Justice Anthony Kennedy in this fashion? I cannot. From Healy's book, on the 1919 Court's initial reaction to Holmes' words:

No one else on the Court wrote like this. Only Holmes could translate the law into such stirring, unforgettable language. Yet even by his high standards this was unusually fine, and his colleagues worried about the effect it might have. Although the war had ended a year earlier, the country was still in a fragile state. There had been race riots that summer, labor strikes that fall. A bomb had exploded on the attorney general's doorstep-- the opening strike, the papers warned, in a grand Bolshevik plot. A dissent like this, from a figure as venerable as Holmes, might weaken the country's resolve and give comfort to the enemy.

The nation's security was at stake, the justices told Holmes. As an old soldier, he should close ranks and set aside his personal views. They even appealed to [Holmes' wife] Fanny, who nodded her head in agreement. The tone of their plea was friendly, even affectionate, and Holmes listened thoughtfully. He had always respected the institution of the Court and more than once had suppressed his own beliefs for the sake of unanimity. But this time he felt a duty to speak his mind. He told his colleagues he regretted he could not join them, and they left without pressing him further.

Three days later, Holmes read his dissent in Abrams v. United States from the bench. As expected, it caused a sensation. Conservatives denounced it as dangerous and extreme. Progressives hailed it as a monument to liberty. And the future of free speech was forever changed.

There have been other instances where a justice changed his mind in a case of profound constitutional import. As Harvard Law School professor Laurence Tribe reminded me this week, Justice Potter Stewart shifted on the issue of reproductive autonomy from dissent in Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965 to the majority in Roe v. Wade in 1973. Justice William J. Brennan shifted on obscenity standards from Roth v. United States in 1957 to Paris Adult Theatre v. Slaton in 1973. Justice Harry Blackmun belatedly changed his mind about the constitutionality of the death penalty. Then there was Justice Owen Roberts' "switch in time" in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish in 1937. None come close to Holmes' "fighting faith" passage.

Judges, and politicians, are too often criticized for changing their minds. Are you not smarter today than you were 10 years ago? Twenty years ago? Have not life's many "experiments" given you wisdom that you did not previously have? The genius of Justice Holmes' dissent in Abrams wasn't just its eloquence it was "meta-ness." He was changing his mind about the need, the value, the glory, the benefit, of changing one's mind and of accepting the changing of other people's minds. Healy has written a magnificent book about a magnificent moment in American legal history -- and in the life of a magnificent man who was smart enough to understand just how wrong people can be.