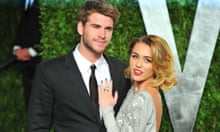

In the star-making Disney Channel switcheroo Hannah Montana, Miley Cyrus played a teenage girl who is able to metamorphose from regular eighth grader to pop icon, simply by donning a streaked blonde wig. Most of the show seems quaintly dated now, but one moment taps into a very 2019 pop anxiety. On The Other Side Of Me. a featherweight single from the programme’s soundtrack album, Cyrus sang: “I flip the script so many times I forget / Who’s on stage, who’s in the mirror.”

Cyrus has shifted her image from foam-finger humper to wholesome cowgirl since, but her new acting role centres again on the self-searching theme of that forgotten 2006 pop classic. In the new season of Black Mirror, Cyrus plays Ashley, a tween-friendly pop star whose latest marketing gimmick is “Ashley Too,” a miniature talking robot toy that replicates both her Pepto-Bismol hairdo and platitude-spouting persona. The episode’s trailer ends with Ashley Too acquiring potty-mouthed sentience, screaming for her owner to “get this [USB] cable out of my ass! Holy Shit!” Specifics are under wraps, but the episode seems centred around a big, knotty question: if someone’s essence can be transplanted into a mechanised clone, where do we end and robots begin?

I’m not saying that Hannah Montana is a millennial Tiresias — a modern-day seer with supernatural visions of the future — but I’m also not not saying that. The binary between man and machine is growing increasingly porous, with virtual assistants like Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa taking up residence in our phones and homes, and growing increasingly humanlike by the day. When instructed to rap, Alexa performs a string of Tom Lehrer-esque nonsense about rocks and sediment. If you ask Siri if she can dance, her response is: “I do a pretty mean robot.” Software that replicates the personality of celebrities may be a while off, but it’s not inconceivable that well-liked celebrities could lend their voices similar products in the future, à la Ashley Too. You can certainly imagine a market for the RuPaul Alexa who tells users to “step your pussy up” every morning.

It’s a given that celebrity image is built on smoke and mirrors. But we’re in a curious spot today, where the music industry is manoeuvering to convince audiences that the veneer of an artist’s presence is a compelling substitute to watching a flesh-and-blood performance. Enter the pop star hologram.

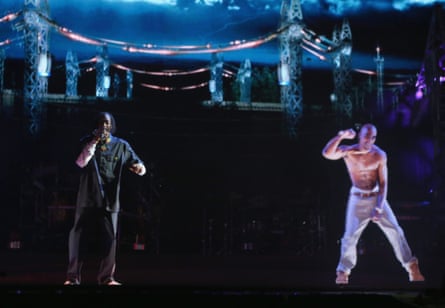

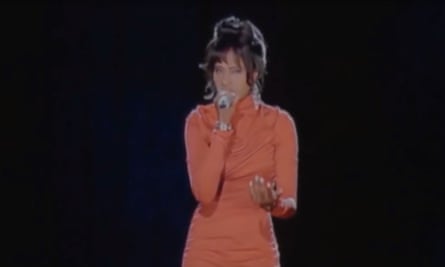

Pop holograms started out as a trompe-l’œil trick. Initially, these rudimentary likenesses weren’t technically holograms at all, but light projections on to a thin piece of glass or gauze that evoked a spectral presence, using a Victorian sideshow technique called Pepper’s Ghost. At the 2006 Grammys, this old ruse was used to make Madonna appear to duet with Gorillaz, before the apparition was swapped out for her spandex-clad real-life counterpart. In the 2010s, Pepper’s Ghost enabled Tupac to rise from the dead at Coachella, Michael Jackson to moonwalk at the VMAs, and Mariah Carey to appear simultaneously in five European cities for a T-Mobile gig in 2011. (“It feels like the whole universe is connected! It’s T-Magic,” she said.) In a sublime bit of kitsch that only she could pull off, Celine Dion duets with a projection of herself in her current Las Vegas residency, and lightly banters with her ephemeral clone. “Come back tomorrow, I’m here every night,” smiles the hologram. “Yeah right!” Dion hits back, as the projection disappears with a swipe of her hand.

Today’s top VR firms have moved on from Pepper’s Ghost techniques to use military-grade lasers to create a kind of humanoid light effigy. In the past couple of years, technological advancements have enabled long-dead artists including Maria Callas, Frank Zappa and Roy Orbison to float on to stages worldwide, often accompanied by a live band. In the wake of a postponed Amy Winehouse tour, last month brought the biggest news in the pop hologram’s young history, with an announcement that Whitney Houston would return to the stage thanks to VFX company Base Hologram — the first in a raft of projects which will also include an album of unreleased music (culled from 1985’s Whitney Houston album sessions) and a Broadway show. “She adored her audiences,” said Pat Houston, Whitney’s sister-in-law and the president of the late singer’s estate. “That’s why we know she would have loved this holographic theatrical concept.”

Would Houston really have loved it, or is this simply a cold-blooded manoeuvre to squeeze every drop of cash from her legacy? The pop star’s cousin Dionne Warwick has already blasted the hologram tour. “It’s surprising to me,” she said. “I think it’s stupid.”

Marty Tudor, CEO of production at Base Hologram, explains that his team has been working on the “elaborate” hologram creation process for a few months now. “We do everything very closely in conjunction with the family, with the estate,” he said. “Frankly, we give them approvals over most of what we do, because we do not want to violate somebody’s legacy.”

The actual process of creating Digi-Whitney is secret, but it essentially involves filming an actor performing every beat of the show, and then mapping her body with Houston’s image. (Think of Andy Serkis against a green screen to create Gollum, and you’re not far off.) Audiences won’t see the real Houston’s movements, but an actor’s studied interpretation of what she was like. Tudor was defensive when confronted with the idea that a hologram of a dead person is, for some, inherently ghoulish. He pointed to the case of Peter Cushing, who was able to appear in 2016’s Star Wars: Rogue One thanks to CGI trickery, even though he died two decades prior: “When you went to see that, and Peter Cushing was all the way through that movie, I guarantee you nobody was thinking about the fact that he’s dead.” Well, apart from the widespread outcry over Cushing’s reanimation, which was described as “a digital indignity” in this newspaper.

Hollywood is catching up to this. Before his death in 2014, Robin Williams made the unprecedented move to create a legal document that safeguarded the use of his image for 25 years after he died. That decision prevents anyone from inserting a CGI Williams into a movie, or, say, putting his hologram in a new Patch Adams Broadway spectacular. Crucially, Williams went as far as to ban even authorised uses of his image, meaning that his wishes will stay watertight even if his estate tries to push something through. A Prince hologram was planned to appear as part of Justin Timberlake’s 2018 Super Bowl performance, but was nixed in the wake of an old interview from 1998 resurfacing in which The Purple One called holograms “demonic.” But few public figures could have Prince’s foresight, or Williams’s meticulousness. (Timberlake ended up projecting Prince on what looked like a giant bed sheet.)

“This is a case where the difference between law and morality is important,” says Robin James, a professor of philosophy, gender studies and music at the University of North Carolina. “Contracts are usually written so that images or recordings can be used in perpetuity, for whatever reason the owner wants. However, compliance with the law is only a small part of ethics. Long-dead people who couldn’t imagine that this sort of tech would ever exist would likely have never consented to this specific use of their work and image.”

In this way, we’re still in what the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori called the “uncanny valley”. Back in 1970, Mori coined the term to describe our repulsion to things that seem almost human, but not quite right. Last year, Base Hologram brought the adored opera singer Maria Callas back to life for string of performances backed by symphony orchestras. Writing of Callas 2.0’s performance in Blacksburg, Virginia, NPR journalist Tom Huizenga described the production’s “absurdities and technical deficiencies” — Callas’s voice was flattened to a blanketing blare, and her hologram bizarrely accepted a proffered “real” rose on stage — as well the unsettling, tear-jerking power of seeing a long-dead diva perform “live”.

Even so, hologram tours do have one indisputable thing going for them: they’re cheap to attend. Pop concerts are pricier than ever, with tickets going for well into the triple digits. Meanwhile, you’ll pay just £60 for the best seat in the house at Base Hologram’s upcoming Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison’s hologram tour, which premieres in the UK this September. For some fans, the novelty factor and affordability will be a worthwhile tradeoff for an imperfect show created without the explicit consent of its star.

For the music journalist and author Simon Reynolds, the wave of hologram tours is an affront to the core notion of live performance. “To what extent are these performances in any real sense?” he asks. “A performance – whether showbiz entertainment or performance art – is by definition live, involving the unmediated presence of living performers, whereas the hologram tours are ‘un-live’ and involve non-presence.

“On an ethical and economic level, I would liken it to a form of ‘ghost slavery’,” he continues. “That applies certainly when done without the consent of the star, [but rather] by the artist’s estate in collusion with the record company or tour promoter. It’s a form of unfair competition: established stars continuing their market domination after death and stifling the opportunities for new artists.”

Prof James agrees. “I’m not sure it’s always going to be fans remembering artists,” she says. “Imagine if there was a Beatles hologram show. With their ongoing popularity, having seen the Beatles in concert won’t be just a boomer thing any more. It could have a sort of flattening or homogenising effect across eras and generations.”

Today’s explosion of hologram tours could sow the seeds for a future in which androids no longer dream of electric sheep, but are manipulated for chart domination. Reynolds imagines the unscrupulous use of technology to capture and replicate performers’ vocal timbre and bodily mannerisms. “You would get a sort of digi-simulacrum of the artist singing new songs, guesting as vocalist or rapper on other people’s records, or appearing in videos or movies,” he says. “In the recording studio, you’d just need the software which would generate the voice.”

Part of live music’s magic thrill is breathing the same air as your pop idol, hearing that night’s vocal tics and jaw-dropping high notes up close, as well as their obligatory groan-worthy stage banter. For many fans, that will remain preferable to a seamless, stitched together performance from a dead artist who never agreed to be reanimated in the first place. Might it be seen as unconscionable to resurrect an artist without their explicit approval, a depressing symptom of greedy music industry vampirism where not even the dead are able to rest in peace?

But hologram technology for current — and consenting — artists offers more enticing possibilities. Executive producer John Canning of Digital Domain, the company that enabled Tupac’s Coachella cameo, predicts that capture and display technology will enable us to watch holographic performances from awards shows like the Grammys in our living rooms. “You can see the glimmers of what is possible when you put on a high-end VR headset,” he says. “That experience is just going to get better.”

Similar technology could also give fabulous depth to pop history. Last year, Beyoncé meticulously recorded her epochal Coachella headline slot for Netflix, creating a electrifying visual and audio archive of a performance which centred black culture and marked her artistic peak. It’s not hard to imagine that she could have created 3D scans of her every ad-libbed gesture and dutty-wine for a global hologram tour of the concert. Would The Beychella Experience have the same magic as the original live performance? No way. Would it redefine the possibilities of concert films? Yep. Would it sell every ticket every time? Absolutely.

Black Mirror season 5 launches on Netflix on 5 June.