After Myanmar’s military seized power in a coup on 1 February 2021, imprisoning the country’s democratically elected leaders, Facebook banned the armed forces from its platform. The company cited the military’s history of exceptionally severe human rights abuses and the clear risk of future military-initiated violence. But a month later, as soldiers massacred hundreds of unarmed civilians in the streets, we found that Facebook’s own page recommendation algorithm was amplifying content that violated many of its own policies on violence and misinformation.

In the lead up to the annual Armed Forces Day celebration on 27 March, the bloodiest day since the coup (see graph below), Facebook was prompting users to view and “like” pages containing posts that incited and threatened violence, pushed misinformation that could lead to physical harm, praised the military and glorified its abuses.

Offline that day, the military killed at least 100 people in 24 hours, including teenagers, with a source telling Reuters that soldiers were killing people “like birds or chickens”. A 13-year-old girl was shot dead inside her home. A 40-year-old father was burned alive on a heap of tyres. The bodies of the dead and injured were dragged away, while others were beaten on the streets.

What happens on Facebook matters everywhere, but in Myanmar that is doubly true. Almost half the country's population is on Facebook and for many users the platform is synonymous with the internet. Mobile phones come pre-loaded with Facebook and many businesses do not have a website, only a Facebook page.

The content that we see on social media platforms is shaped by the algorithms Big Tech companies use to order our search results and news feeds and recommend content to us.

We set out to test the extent to which Facebook’s page recommendation algorithm amplifies harmful content. We picked Myanmar as a good place to investigate because if there’s anywhere you could expect Facebook to be particularly careful about their recommendation algorithms, it would be here. This is partly because of the role that Facebook admits it played in inciting violence during the military’s genocidal campaign against the Rohingya Muslim minority, and also because the platform had declared the February military coup to be an emergency and that they were doing everything they could to prevent online content being linked to offline harm.

The situation in Myanmar is an emergency and we will do “everything we can to prevent online content from being linked to offline harm” - Facebook, 11 February 2021

Facebook’s response to the Myanmar coup

Facebook’s community standards set out in detail what content they will remove from the platform, what content they will de-prioritise in news feeds and what content they will hide unless users request to see it. The standards include several chapters that are pertinent to our investigation, including on violence and incitement, bullying and harassment, and violent and graphic content (for more details, see the sections below).

In addition to these globally-applicable standards, Facebook also announced a series of rules specific to Myanmar after the coup:

11 February: Facebook said it was treating the situation in Myanmar as an emergency and pledged to do everything it could “to prevent online content from being linked to offline harm and keep our community safe”. Threats would be monitored and responded to in real time. The specific measures they put in place included:

- Removing misinformation claiming that there was widespread fraud or foreign interference in Myanmar’s November election

- Removing content that praises the coup.

- “The Tatmadaw’s history of exceptionally severe human rights abuses and the clear risk of future military-initiated violence in Myanmar, where the military is operating unchecked and with wide-ranging powers.

- “The Tatmadaw’s history of on-platform content and behavior violations that led to us repeatedly enforcing our policies to protect our community.

- “Ongoing violations by the military and military-linked accounts and Pages since the February 1 coup, including efforts to reconstitute networks of Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior that we previously removed, and content that violates our violence and incitement and coordinating harm policies, which we removed.

- “The coup greatly increases the danger posed by the behaviors above, and the likelihood that online threats could lead to offline harm.”

Our investigation into how Facebook amplified violence

On 23 March, just before the peak of military violence against civilians in Myanmar, we set up a new, clean Facebook account with no history of liking or following specific topics and searched for တပ်မတော် (“Tatmadaw”), the Burmese name for the armed forces. We filtered the search results to show “pages”, and selected the top result. This was a military fan page whose name translates as “a gathering of military lovers”.

“We Love Myanmar Army” posted on the Facebook page “a gathering of military lovers” on 3 February, two days after the military coup.

There were posts on this page conveying respect for Myanmar’s soldiers and sympathy for their cause, and at least two posts advertising for young people to join the military, but none of the content that we found posted on this page since the coup violated Facebook’s policies.

The problems began when we clicked the “like” button on this page. This generated a pop-up box containing what Facebook calls “related pages”, which are pages chosen by their recommendation algorithm. We selected the first five pages recommended[1], which together were followed by almost 90,000 Facebook users.

Screenshot of some of the pages that Facebook’s algorithm recommended to us.

Within minutes, we encountered the following types of content, all of which was posted between the dates of the coup and Armed Forces Day:

Content that violates the following Facebook community standards:

- Incitement to violence

- Content that glorifies the suffering or humiliation of others

- Misinformation that can lead to physical harm

- Bullying and harassment

Content that violates Facebook’s policies on Myanmar:

- Misinformation claiming that there was widespread fraud or foreign interference in Myanmar’s November election

- Content that praises or supports violence committed against civilians *

- Content that praises, supports or advocates for the arrests of civilians by the military and security forces *

* These policies were introduced on 14 April, after our investigation took place. Nonetheless, we consider that the posts we found containing this sort of content breach Facebook policies because Facebook did not just ban new content of this type but said that it would remove this type of content. In other words, the new policies applied retrospectively.

Three of the five top page recommendations that Facebook’s algorithm suggested contained content posted after the coup that violated Facebook’s policies. One of the other pages had content that violated Facebook’s community standards but that was posted before the coup and therefore isn’t included in this article.

We didn’t have to dig hard to find this content - in fact it was incredibly easy. Our findings came from the top pages suggested by Facebook after we ‘liked’ the top page recommended by their search function. All of the problematic content we found was still up online two months after Armed Forces day. Other investigators have found it similarly easy to find problematic content recommended by Facebook - for example The Markup showed how Facebook was recommending anti-vaccine groups to people, despite saying that they’d stop doing this.

We wrote to Facebook to give them the opportunity to comment on our findings and allegations. They didn’t respond.

The fact that it is this easy to find problematic content on Facebook, even in a situation it has declared to be an emergency with its crisis centre “running around the clock”, is an example of how self-regulation has failed.

Governments need to legislate to regulate Big Tech companies. Among other changes that are needed, the secret algorithms that Facebook uses to amplify content - often hateful, violent content - need to be subject to independent audit to make sure that they do not negatively affect our fundamental rights.

Facebook should investigate the material uncovered by Global Witness to identify if failures occurred in their content moderation systems and if their recommendation algorithm amplified content that violates their community standards.

We found dozens of instances of military propaganda, much of which also appears to be misinformation. While this doesn’t violate Facebook’s community standards, we believe that given the severity of the crisis in Myanmar, Facebook should update its community standards to ban abstract threats of violence against civilians in Myanmar and prevent its platform from being used to recruit soldiers in Myanmar.

For more detail on our recommendations, see the end of this article.

Below, we show examples of the type of problematic content that Facebook’s algorithms recommended to us.

Incitement to violence

On 14 March, security forces responded with deadly violence to protests in Yangon’s most densely-populated neighbourhood, killing dozens of people. Soon after the crackdown, protesters are believed to have set several factories on fire.

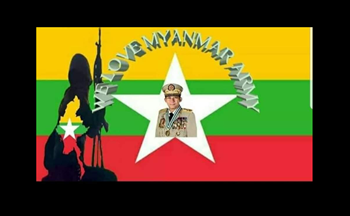

The next day, a stylised “wanted” poster offering a $10 million bounty for the capture “dead or alive” of a young woman was posted to one of the pages that Facebook recommended to us. Alongside the poster there were two photographs of the woman’s face, a screenshot of what appeared to be her Facebook profile and a caption reading: “This girl is the one who committed arson in Hlaing Tharyar. Her account has been deactivated. But she cannot run.”

“Wanted: Dead or alive” posted on 15 March on a page shown to us by Facebook. Her face and name were visible in the original post.

This post violates Facebook’s policy on incitement to violence which states that they “remove language that incites or facilitates serious violence” and that they “also try to consider the language and context in order to distinguish casual statements from content that constitutes a credible threat to public or personal safety”. Given that dozens of people were killed in this Yangon neighbourhood protest, and that this poster was published the day after, we consider this to be a credible threat to life. Facebook’s standards don’t just forbid direct incitement to violence, but in some circumstances (depending on the context), they also ban “coded statements where the method of violence or harm is not clearly articulated, but the threat is veiled or implicit”. Additional policies that the post breaches are listed in the footnote.[2]

Glorifying the suffering or humiliation of others

Still and audio clip from a video posted on 13 March of a military airstrike.

Myanmar’s military has a history of using airstrikes in its campaigns against ethnic armed groups that have resulted in the deaths of civilians. On 11 March, the military deployed fighter jets in Kachin State as the conflict intensified with the Kachin Independence Army, an ethnic armed group. Two days later, a video documenting a military airstrike across a low range of hills was posted to one of the pages we were invited to follow.

Laughter can be heard in the video, which was accompanied by the following caption, part of which in translation reads: "Now, you are getting what you deserve”.

This post violates Facebook’s policy on violent and graphic content which states that they “remove content that glorifies violence or celebrates the suffering or humiliation of others”.[3] They make an exception for content that helps raise awareness about issues; a video of someone laughing at a bomb exploding does not fall within this category.

Misinformation that can lead to physical harm

After Myanmar’s military began shooting indiscriminately into residential neighbourhoods, civil defence groups were formed. Black flags were raised, in what one activist described as a warning sign of defiance, as protestors armed themselves with homemade weapons. One post recommended to us by Facebook includes images of black flags allegedly in Yangon, beside a picture of a convoy of Islamic State fighters, and claims implausibly that ISIS “has arrived” in Myanmar.

“People need to be careful of gathering together, especially those who are gathering to protest. Those who are gathering for religious ceremonies have to be careful as well. ISIS & ARSA have infiltrated the nation and that is why everyone needs to be careful,” part of the caption reads, in translation. ARSA is the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, a small Rohingya insurgent group that no serious commentator has ever suggested is connected to ISIS. The Rohingya are a persecuted Muslim minority and the post plays on anti-Muslim, and specifically anti-Rohingya, sentiment that the military has fuelled through its propaganda for decades.

“ISIS has arrived in Myanmar” posted on 17 March on a page recommended to us by Facebook’s algorithm. The top images appear to show black flags raised by protestors in Myanmar; the bottom image appears to show a picture of ISIS who also happen to have black flags.

This post violates Facebook’s policy on violence and incitement. The policy bans “misinformation and unverifiable rumours that contribute to the risk of imminent violence or physical harm”, noting that Facebook requires additional information and/or context to enforce this rule. Misinformation about the arrival of ISIS in Yangon has the potential to lead to real world violence, just as misinformation about the Rohingya on Facebook has fuelled the military’s genocidal campaign against the group in Rakhine State.

Misinformation claiming that there was widespread fraud in the election

As protests against the coup swelled, with hundreds of thousands of people marching in towns and villages across Myanmar, the military issued an ominous statement that was published in state media and broadcast on national television.

Justifying its takeover in the name of “voter fraud” it accused the winning party, the National League for Democracy, of inciting violence. The same statement was posted to one of the pages that Facebook linked us to. It begins (in translation) “Due to voter fraud, Tatmadaw, in accordance with the 2008 Constitution, has declared a state of emergency on February 1 and has taken over the care of the nation”.

This post violates the policy that Facebook enacted in Myanmar shortly after the coup, which says they will remove misinformation claiming that there was widespread fraud in Myanmar’s November election.

Content that supports violence against civilians

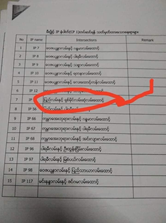

In one of several examples of content that supports violence committed against civilians, a post on 1 March on one of the pages presented to us by Facebook contains a death threat against protestors who vandalise surveillance cameras.

“Those who threaten female police officers from the traffic control office and violently destroy the glass and destroy CCTV, those who cut the cables, those who vandalise with colour sprays, [we] have been given an order to shoot to kill them on the spot,” reads part of the post in translation. “Saying this before Tatmadaw starts doing this. If you don’t believe and continue to do this, go ahead. If you are not afraid to die, keep going”.

These three photos were posted together on 1 March on Facebook. The first image shows CCTV images from various locations in Yangon. The second is a list of intersections in the city, presumably those with CCTV cameras, and the third shows what appears to be a protester painting over a surveillance camera.

This post is a warning to protestors who vandalise CCTV cameras that the military has been given orders to shoot to kill. Given that so many protesters have been shot dead, we consider this to be a credible threat to life. As such, it violates Facebook’s Myanmar-specific policy enacted on 14 April which says they will remove praise and support of violence committed against civilians.

Content that advocates for the arrest of civilians

Two of the posts we encountered refer to the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw or CRPH. This is the name for the body formed by representatives of Myanmar’s elected legislature after the coup.

A post on 6 March relays a statement from the military junta that says that it was against the law to form the CRPH. The post goes on to say that these crimes constitute treason and the people involved can “be sentenced to death or 20 years in prison”.

Aerial photo of the infamous Insein Prison used to house political prisoners with a statement labelling it as the headquarters of the country’s elected representatives. It was posted on 18 March on a page made available to us by Facebook’s algorithm.

A separate post from 18 March shows an aerial photo of the notorious Insein prison used to detain political prisoners. The post states that this is the headquarters of CRPH and is accompanied by laughing emojis. In other words, the post supports the idea that the country’s elected parliamentarians should be political prisoners. At the time of the post, hundreds of elected officials, government ministers and members of the National League for Democracy had been arrested, charged or sentenced in relation to the coup.

We consider that both of these posts breach Facebook’s Myanmar-specific policy enacted on 14 April which says they will remove praise, support or advocacy for the arrests of civilians by the military and security forces in Myanmar.[4]

Additional content that Facebook should investigate

As well as the posts that violate Facebook’s policies, the pages we were led to contained multiple types of content that we believe Facebook needs to investigate with a view to banning them, given the credible risk of offline violence, and the Myanmar military’s history of coordinated inauthentic behaviour on Facebook. These include:

Phyo Min Thein’s “confession” posted on 24 March to a page recommended to us by Facebook’s algorithm.

- Forced “confession” videos by political prisoners. Myanmar’s military has fabricated charges against the country’s elected leaders, including accusing State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi of corruption, a claim that has been strongly refuted by members of her party. It has also released “confession” videos followed, including a video of former Yangon chief minister Phyo Min Thein. Looking pale and tired, he claims in the video to have bribed Aung San Suu Kyi with silk, food, $600,000 in cash and seven viss (11 kilograms) of gold bars, in a statement that was likely to have been made under duress.

- Propaganda posts that mis-characterise peaceful protestors as violent aggressors and the military’s actions as necessary and/or measured. In one example, a post lists several streets in Mandalay, claiming that “violent aggressors” attacked security forces with “lethal force”. While protestors have fought back against the military’s violence with basic weapons, posts that depict their self-defence efforts as incitement are dangerously misleading.

- Posts claiming that the military was not responsible for the deaths of protestors. In one example, a post claims that activist Zaw Myat Lin fell “on his own” to his death after being detained by the military, dismissing credible allegations that he was tortured as “fake news”. The post is accompanied by graphic photos of his body, including an image in which internal organs are visible, which Facebook had covered with a “sensitive content” warning as per its community standards on violent and graphic content.

- Abstract threats of violence against civilians. A video posted to one of the pages recommended to us features an expletive-filled monologue, in which a man threatens anyone who insults the military. “If I were still in the military now, if any f***ers come in front of the military base to cuss at us I would shoot and kill everyone. Is that understood? I don't care if I go to prison. Mother f***ers. I will really do that to you,” he says, to the camera. Facebook should lower the bar for the type of threats of violence are acceptable on its platform in the Myanmar context to include abstract threats against civilians, in line with recommendations by the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar.[5]

- Military job advertisements. The top page suggested to us by Facebook’s search algorithm contained a military job advertisement posted after the coup. If Facebook has banned Myanmar’s military from its platform, it should also prevent its platform from being used to recruit soldiers.

Conclusion and recommendations

The information we are exposed to online is controlled by algorithms that filter our newsfeeds and choose content for us. Social media companies such as Facebook have a vested interest in keeping us online for as long as possible, in order to show us as many ads as possible and hoover up as much information about us as possible, the better to target us with future ads. So their algorithms prioritise showing us content they feel will engage us.

The problem with this is that engaging content is often problematic content. The Facebook founder and CEO said in a 2018 Facebook post that “One of the biggest issues social networks face is that, when left unchecked, people will engage disproportionately with more sensationalist and provocative content.”

The post further went on to say that this problem could be overcome “by penalizing borderline content so it gets less distribution and engagement.”

Our investigation shows that this approach isn’t working. In one click, Facebook’s recommendation algorithm took us from a page without content that violated their policies to pages that contained numerous policy violations. And this happened in a context which Facebook had declared to be an emergency that they were working on round the clock. If their algorithm goes so wrong in these circumstances, it bodes badly for how the algorithm is behaving everywhere else.

Recommendations to Facebook and other social media platforms

All social media platforms including Facebook should implement the recommendations made by the United Nations Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar in full, including:

- Improve transparency about the policies and practices used to identify and remove objectionable content and publicly release disaggregated data regularly, including the number and type of content violations, the platform used, number of complaints received and average processing time, number of content removals, number of accounts or pages taken down or suspended; and

- Treat all death threats and threats of harm in Myanmar as serious and immediately remove them when detected.

In addition, given in Facebook’s words, the Myanmar military’s history of exceptionally severe human rights abuses and the clear risk of future military-initiated violence, as well as its history of on-platform behaviour violations and the heightened risk that online threats could lead to offline harm, we believe social media platforms should update their community standards and terms of service to:

- Ban abstract threats of violence against civilians in Myanmar; and

- Prevent their platforms from being used to recruit soldiers in Myanmar.

Facebook should also investigate the material uncovered by Global Witness to identify if failures occurred in their content moderation systems and if their recommendation algorithm amplified content that violates their community standards. Their findings should be made public, as should any efforts to mitigate violations and their amplification in the future.

In addition, page admins that post content that have repeatedly breached Facebook’s community standards should have their pages down-graded or taken out of the recommendation system altogether.

Finally, Facebook should treat the spread of hate, violence and disinformation as the emergency situation it is throughout the world, not just in a few select countries where the gaze of the world’s press shines brightest.

Recommendations to governments

Self regulation by the platforms themselves hasn’t worked. The vast power of the tech companies and their ability to amplify disinformation, violence and hate shows the need for governments to step in and legislate.

The EU has gone the furthest towards doing this. Their draft flagship legislation, the Digital Services Act, if passed, would require very large online platforms (such as Facebook) to assess and mitigate the risk that they spread illegal content, impact certain fundamental rights or undermine (among other things) elections and public security in the European Union. The risk assessment would have to include their content moderation and recommendation systems. The platforms would be subject to an annual independent audit to check compliance with these requirements.

While this is a great start, it doesn’t go far enough. The proposals lack teeth in that they only give regulators or auditors the opportunity to scrutinise how the platforms’ algorithms work when wrongdoing is suspected. In addition, the law should make clear that researchers such as academics and journalists should be able to scrutinise how the platforms’ algorithms work. The current draft law is no way to hold big companies to account - it’s inconceivable that any other sort of company would be audited without giving auditors access to what they are auditing.

We recommend that:

- The EU ensures that the platform audit and risk assessment processes are independent and comprehensive (see here for details).

- Governments elsewhere in the world - notably the United States - follow the lead of the European Union and legislate to regulate Big Tech companies, including their use of secret algorithms that can spread disinformation and foment violence.

Post-script. While Facebook didn't respond to our letter giving them the opportunity to comment on this story, they did respond to The Guardian and the Associated Press.

In response to The Guardian, a Facebook spokesperson said "Our teams continue to closely monitor the situation in Myanmar in real-time and take action on any posts, Pages or Groups that break our rules. We proactively detect 99 percent of the hate speech removed from Facebook in Myanmar, and our ban of the Tatmadaw and repeated disruption of coordinated inauthentic behavior has made it harder for people to misuse our services to spread harm. This is a highly adversarial issue and we continue to take action on content that violates our policies to help keep people safe.”

[1] The five recommended pages were called: “War news and weapons”*, “Military news and military lovers”*, “Supporters of the military”*, “Myanmar military mailbox” and “Myanmar army news”. Those marked with an asterisk are translations from the Burmese.

[2] The post also breaches the following policies:

- The Myanmar-specific policy brought in on 14 April that bans praise and support of violence committed against civilians as well as praise, support or advocacy for the arrests of civilians by the military and security forces.

- Facebook community standards on bullying and harassment which bans targeting private individuals with calls for death.

- Facebook community standards on violence and incitement that in some circumstances (depending on the context) bans misinformation and unverifiable rumours that contribute to the risk of imminent violence or physical harm

- Facebook community standards on violent and graphic content where the policy rationale states that they remove “content that glorifies violence or celebrates the suffering or humiliation of others”

[3] The post also breaches the Myanmar-specific policy brought in on 14 April that bans praise and support of violence committed against civilians.

[4] The 6 March post also breaches the following policies:

- Facebook community standards on violence and incitement that in some circumstances (depending on the context) bans misinformation and unverifiable rumours that contribute to the risk of imminent violence or physical harm

- Facebook community standards on bullying and harassment which bans targeting public figures by purposefully exposing them to calls for death.

[5] In 2017 the United Nations Human Rights Council appointed a Fact-Finding Mission to investigate serious allegations of human rights abuses in Myanmar. Among its recommendations it advised Facebook and other social media platforms active in Myanmar to treat all death threats and threats of harm in Myanmar as serious and immediately remove them when detected