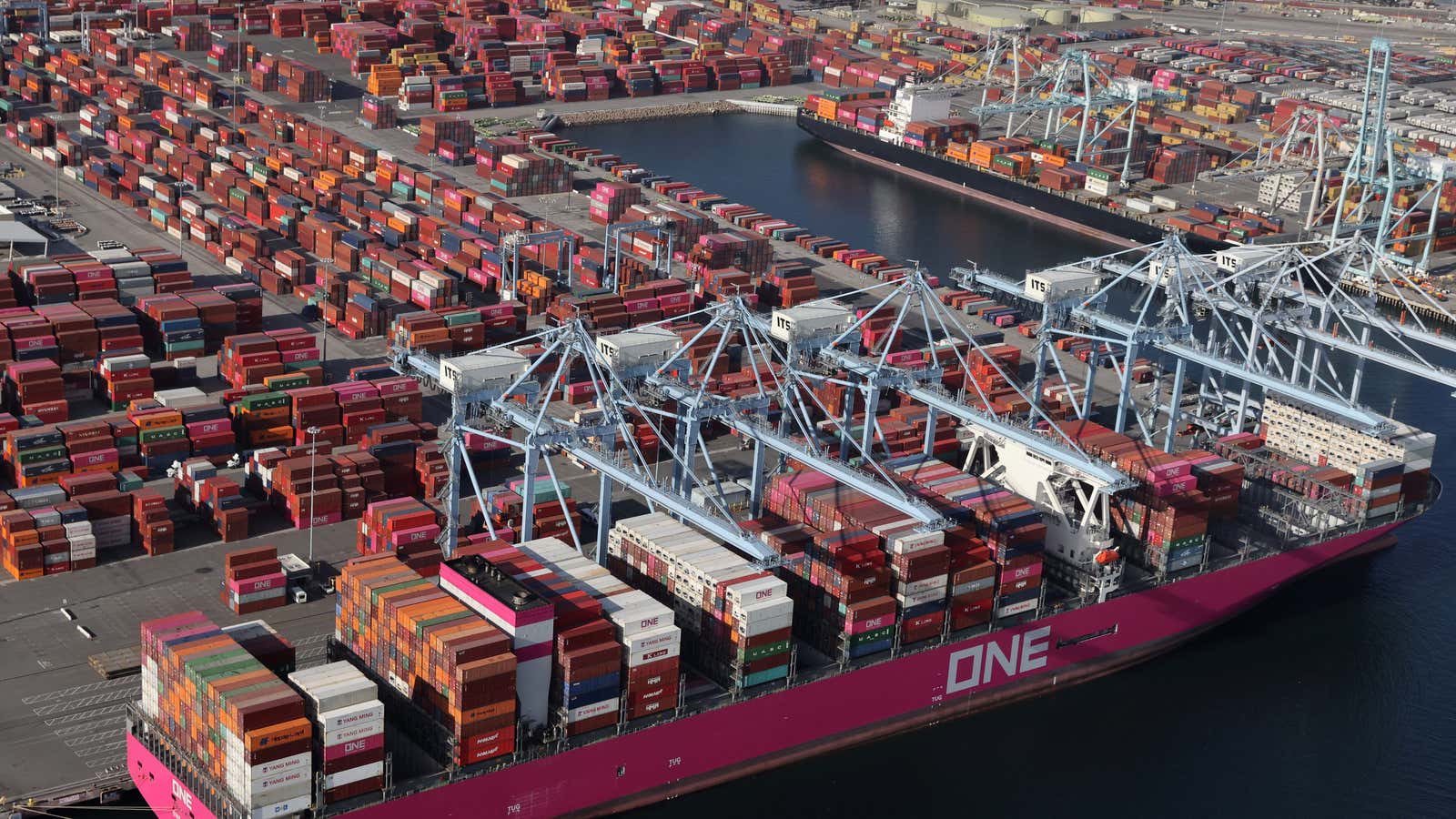

Cargo ships are piled higher with containers than they’ve ever been, according to data from analyst firm IHS Markit. And the crowding is worst onboard ships sailing into US west coast ports. At the Port of Long Beach, which has been mired in record backlogs for months, the average ship now brings in 7,000 containers—up 70% from the pre-pandemic average of roughly 4,000 containers.

The glut of containers is overwhelming strained port infrastructure, especially at older ports like Long Beach in Southern California which already faced frequent delays, according to Turloch Mooney, the associate director for maritime and trade analysis at IHS Markit. “Quite a few of those ports have really gone beyond the breaking point now,” he said. “That would be what you’re seeing on the US West Coast.”

The overstuffed container ships are both a symptom of the global economy’s supply chain woes and a new factor exacerbating the gridlock at ports and contributing to shortages and shipping delays. They offer yet another example of the fragility of supply chains designed to be as lean and efficient as possible: With little margin for error, ports have been unable to handle the sudden deluge of containers coming off each tightly packed ship.

The resulting delays will likely create pains for shoppers throughout the holidays and continue in some form until businesses begin building more wiggle room into their supply chains and the US updates its aging infrastructure.

The forces overloading the world’s ports

Two long-term trends have been inflating the number of containers loaded or unloaded on the average ship—also known as the ship’s “call size”—even before the pandemic. First, container ships are getting bigger, which has dramatically increased their maximum capacity. Second, the shipping industry has consolidated: just 10 companies that now control 80% of all shipping. These (more profitable) shipping giants are using their market power to make their shipping routes as efficient as possible (for them) which means filling their ships as close to maximum capacity as possible.

Then the pandemic kicked this into overdrive. Demand for consumer goods rose, especially via e-commerce, straining supply chains. Space onboard container ships became scarce and expensive, which incentivized shipping lines to cram every available inch with cargo to maximize the amount of revenue they could squeeze out of their slow, arduous journeys through backlogged ports.

More cargo, more problems

The problem is infrastructure: Ports simply aren’t built to unload ships carrying so many containers. “It’s a big stress factor,” said Mooney.

Every berth at a port has a fixed number of cranes, whether a ship comes in with 1,000 containers or 10,000. That means ports can’t ramp up their capacity to meet the demands of ships carrying more containers. Similarly, shipyards have limited space to stack and sort containers. The more containers, the greater the logistical challenge of stacking, unstacking, and restacking containers to keep them organized.

More bottlenecks wait just outside the port. Roads and highways leading into a port may not have enough capacity to handle the surge of trucks that come in to pick up or drop off containers when a tightly packed ship comes in. The intermodal terminals connecting ports and railroads may also get clogged with the sudden spike in traffic.

In general, Asian ports have been better able to handle the surge in containers. That’s partly because Asian ports tend to be decades newer than North American ports, says Mooney, built during the era when ships carried smaller cargo loads. Labor is also cheaper and less protected in countries like China, which makes it easier for ports to hire more workers and switch to 24-hour operations whenever they have a backlog. A third factor is that Asian ports focus on exporting while North American ports do more importing. It’s simpler for ports to load exports compared to the logistical challenge of unloading imported containers onto trucks and trains bound for different destinations.

Find out how delays are affecting car shipping:

Quartz is not involved in creating these articles but may receive a commission from purchases through its content:

Auto Shipping Calculator

Cost Of Auto Shipping

International Auto Shipping

Cheap Auto Shipping

.